A companion to

On Photography by Susan Sontag

Annotations by Fritz Swanson

Susan Sontag, as painted in 1994 by Juan Bastos

Links to the Annotations, Sorted by Essay

The Essays:

- "In Plato's Cave" (Page 3-24)

- "America, Seen Through Photographs, Darkly" (Page 27-48)

- "Melancholy Objects" (Page 51-82)

- "The Heroism of Vision" (Page 85-112)

- "Photographic Evangels" (Page 115-149)

- "The Image-World" (Page 153-180)

- "A Brief Anthology of Quotations" (Page 183-208)

- BONUS: Did Sontag steal all her best ideas from The Kinks? Scholars remain divided.

An Introduction to the Annotations

Beginning in 1973 and finishing in 1977, Susan Sontag set about writing a series of 6 essays on Photography for the New York Review of Books. Though the text is a work of criticism in a broad sense, it is not academic. There is no bibliography, and the works cited in the text are dealt with briskly, treating the previous 100+ years of photography as a whole corpus which the reader is presumed to be familiar with. She will refer to dozens, or even hundreds of works in a single clause.It might be better to see the work as an abstract artistic enterprise, as much as it is an intellectual one. Or rather, it seems to conform to her own "sensualistic" view of criticism. As she famously said in her essay "Against Interpretation" "in place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art." (Which is to say, in part, that we have to remember that art is for pleasure, and not just for critics to pick apart as an intellectual exercise.)

While this may not exactly be an "erotics" of Photography, it may be something like a poetic response to Photography as a whole discipline up to the point of her last essay, published in 1977. However you might define the work, it was well respected in its day, and profoundly influential, winning the National Book Critics' Circle Award for Criticism (1977).

I think the simpler description of the work is that it is a very educated, idiosyncratic and intense view of the art of Photography. Such a view can be contained in one mind because the art in question is so young, and its main practisioners are so few. As a consequence, reading the book is a bit like being cornered at a party by an extremely engaging, and very intense enthusiast who has about six hours of ideas she wants to convey to you in a single gulp of air. The whole time she is racing charmingly through her thesis, she presumes you should, and do, know every reference she is making, and you are too polite (and perhaps too embarrased) to correct her and ask for any clarifications and expansions.

And so, once you have disengaged from the mad woman at the party with all the wonderful ideas, you stumble away wishing you had taken notes, or that she had brought along a powerpoint presentation, or better that she could have, while talking, assembled a private museum for your personal viewing, and that she could have been the tour guide to lead you through.

Given that I very much wish I had been at that party, I have here started to assemble something of that Museum that would be necessary to fully appreciate what on earth she is banging on about.

I am using the Picador edition of ON PHOTOGRAPHY. ISBN: 9780312420093

My process has been to go through the book and highlight every direct reference to an art object or document. She's pretty clear about what she is talking about. Then I have made a list of the references below, in the order they appear in the book. Finally I have associated each item with a collection of links. Some of the links provide general context, some point to specific works of art. If a specific image is cited in the book, I have done my best to present that exact image here on the page.

The goal is that you should be able to read the book with this page open, and as Sontag proceeds through her argument, you should be able to scroll down through as many of the images as I can find. And if you want to pause and dig deeper into a specific artist or historic moment, you will have the links I think you will need to do that.

The book is a slender 200 pages. What I find so compelling about it is that if you take the time to parse all of its citations you will receive a very full education on the history of photography up to 1977, as well as an interesting cursory view of American history from the Victorian period to 1977. I think this says something very simple and very true about good criticism: it should be the fine point of a massive pyramid of thought.

Why bother to read this book, or care about these annotations? Because Sontag's prescient views both predicted and DEFINED what the next generation thought about photography. And since photography has become more rather than less important, Sontag becomes an essential starting point and touchstone for thinking about our present world. Sontag died the same year Facebook was founded, six years before Instagram was founded, and 10 years before the rise of TikTok.

Sontag herself inadvertently sets the standard for her own success when she paraphrases T.S. Eliot saying, "Each important new work necessarily alters our perception of the past." On Photograohy does that.

As you read Sontag, ask yourself, What would Sontag think of our world? What is consistent with her views? What defies her views? What takes her ideas, but complicates them in ways she could not have anticipated?

Just take any paragraph out of this book, and set it down next to any modern image and see what ideas are sparked for you.

(I hand coded this single page of annotations in HTML in the Summer of 2020. Material updates will be noted here.)

Susan Sontag, at a party, about to launch into a three hour rant about Diane Arbus and Walt Whitman

The Essays:

- "In Plato's Cave" (Page 3-24)

- "America, Seen Through Photographs, Darkly" (Page 27-48)

- "Melancholy Objects" (Page 51-82)

- "The Heroism of Vision" (Page 85-112)

- "Photographic Evangels" (Page 115-149)

- "The Image-World" (Page 153-180)

- "A Brief Anthology of Quotations" (Page 183-208)

"In Plato's Cave" (Page 3-24)

- Plato's Cave

- Do we see reality? Or do we merely see its shadow? Are images a way to see reality? Or do they distort and obscure reality? If we can see reality, can we communicate what we see to others?

- "The Allegory of the Cave" from Plato's Republic. Translated by Thomas Sheehan

- "The Allegory of the Cave" on Wikipedia

- Les Carabiniers by Godard (1963)

- "The Carabineers" as described by Wikipedia

- IMDB on The Carabineers

- You can check out Les carabiniers un film de Jean-Luc Godard from our library.

- Si j'avais quatre dromadaires by Chris Marker (1966)

- Paris Communards June 1871

- Alfred Stieglitz

- Wikipedia on Stieglitz

- MOMA on Stieglitz

- MET on Stieglitz

- Chicago Art Inst. on Stieglitz

- International Center for Photography (ICP) on Stieglitz

- Paul Strand

- Farm Security Administrations Photographs (1930s)

- The Library of Congress collection of these images

- Wikipedia on the FSA

- PDF Summary of the FSA from the US Government

- Walker Evans

- Dorothea Lange

- Wikipedia on Lange

- MOMA on Lange

- ICP on Lange

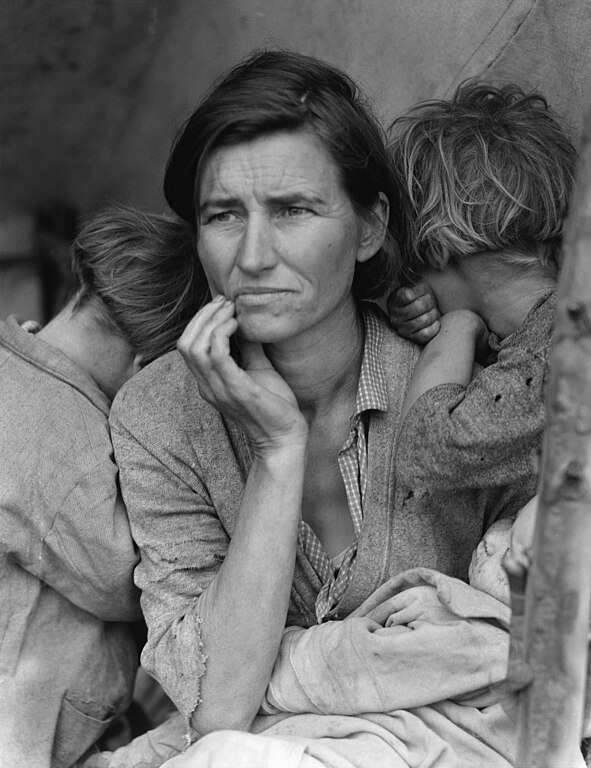

Migrant Mother (1936)- Ben Shahn

- Russell Lee

- David Octavius Hill

- Julia Margaret Cameron

- Leica Ad

- Photojournalism page 11

- Man with a Movie Camera by Dziga Vertov (1929)

- Rear Window by Alfred Hitchcock (1954)

- Diane Arbus

- Blowup by Antonioni (1966)

- Peeping Tom by Michael Powell (1960)

- Yashica Ad page 14

- Samuel Butler

- memento mori

- Wikipedia on memento mori

- "A memento mori (Latin 'remember that you [have to] die') is an artistic or symbolic reminder of the inevitability of death. The expression 'memento mori' developed with the growth of Christianity, which emphasized Heaven, Hell, and salvation of the soul in the afterlife."

- Eugene Atget

- Brassai

- Mathew Brady Civil War Photos

- National Archives Collection of Brady Civil War Photos

- Wikipedia about Brady

Scene showing deserted camp and wounded soldier (Zouave), 1865(?)- Andersonville

- "The Andersonville National Historic Site, located near Andersonville, Georgia, preserves the former Andersonville Prison (also known as Camp Sumter), a Confederate prisoner-of-war camp during the final fourteen months of the American Civil War. Most of the site lies in southwestern Macon County, adjacent to the east side of the town of Andersonville. As well as the former prison, the site contains the Andersonville National Cemetery and the National Prisoner of War Museum. The prison was made in February 1864 and served to April 1865."

- Wikipedia on Andersonville, Confederate Prisoner Camp

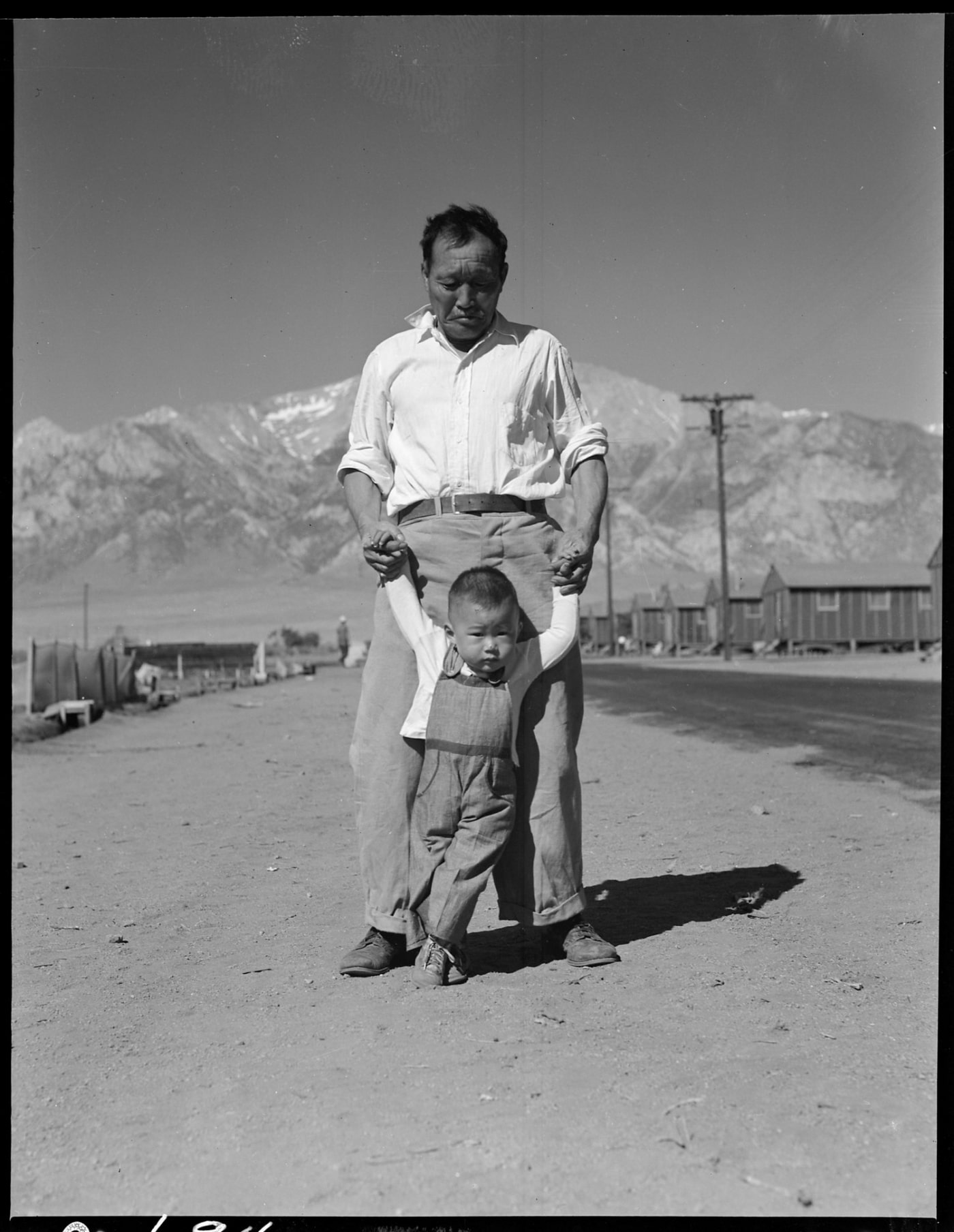

[Unidentified emaciated prisoner of war, released from prison at Belle Isle, Richmond, at the U.S. General Hospital, Div. 1, Annapolis]- Dorothea Lange Nisei 1942 internment camps

- 1972 Nick Ut photo girl

- Felix Greene

- Marc Riboud

- Hanoi

- Don McCullin's photos of Biafrans 1970s

- Werner Bischof's Indian famine 1950s

- Tuareg famine 1973

- Gulag Archipelago

- Daily News

- Le Monde

- faits divers

- Jacob Riis New York 1880s

- Wikipedia on How the Other Half Lives

- Wikipedia on Riis

- Library of Congress Exhibit on Riis and "How the Other Half Live"

- Brecht Krupp Photo

- This quote from Brecht originates in Walter Benjamin's A Short History of Photography (1931)

- Another copy of the Benjamin piece

- A Third copy

- Here is the quote as it appears in Benjamin's essay: "As Brecht says: "The situation is complicated by the fact that less than ever does the mere reflection of reality reveal anything about reality. A photograph of the Krupp works or the AEG tells us next to nothing about these institutions. Actual reality has slipped into the functional. The reification of human relations--the factory, say--means that they are no longer explicit. So something must in fact be built up, something artificial, posed.""

- Wikipedia on Symbolist Poet Stephane Mallarme

"America, Seen Through Photographs, Darkly" (Page 27-48)

- Walt Whitman Leaves of Grass Introduction (1855)

- Cultural Revolution and the Red Guard

- Edward Steichen Photo of Milk Bottle 1915

- Andy Warhol

- Walker Evans MOMA Book Epigraph from Whitman

- American Photographs by Walker Evans on AbeBooks

- PDF of selections from the book

- (I can't easily find the actual quote. I will add this later.)

- Camera Work by Stieglitz (1903-1917)

- Little Gallery of the Photo-Secession, later 291 (New York, 5th Avenue 291. 1905-1917)

- Walker Evans

- Lewis Hine photos of immigrants and workers

- Wikipedia on Hine

Climbing into the Promised Land, Ellis Island (1908)

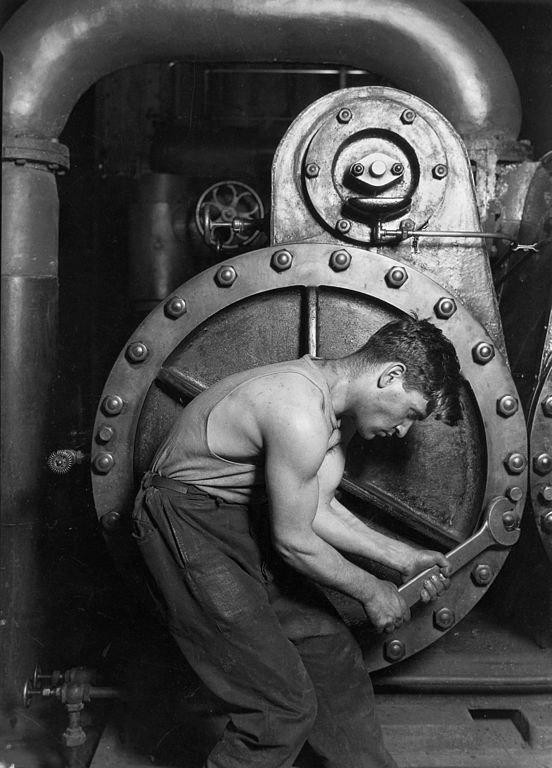

Power house mechanic working on steam pump. (1920)- Evans secret subway photos 1939-1941

- Port of New York (1924) Paul Rosenfeld

- Evans architectural photos

[Brooklyn Bridge, New York] (1929)- Southern Sharecroppers

- Let Us Now Praise Famous Men by Walker Evans and James Agee

- Evans

- "Family of Man" exhibit organized by Edward Steichen in 1955

- Diane Arbus work in 1972 MOMA Retrospective

- Bunuel making movies

- Arbus Photos

- Arbus images on ArtNet

- Drag balls

- welfare hotels

- Maryland carnival

- human pincushion

hermaphrodite with a dog- tatooed man

- albino sword swallower

- nudist camp in New Jersey and Pennsylvania

Disneyland

Disneyland

Hollywood set

mental hospital (An article in Sleek Magazine features these images)- crying babies

two girls in Central Park in identical raincoats

twins and triplets- nudist camp waitress in apron

- boy with straw boater and bomb hanoi button

king and queen of a senior citizens dance- thirtyish suburban couple sprawled on their lawn

- a jewish giant at home with his parents in Bronx, NY, 1970

- Julia Margaret Cameron Victorian portraits

- Wikipedia on Julia Cameron

Charles Darwin

Alice Liddell (friend of Lewis Carroll, possible basis for Wonderland Alice)- Hegel "unhappy consciousness"

- Grand Guignol

- More Arbus

- female impersonators

- mexican dwarf in his manhattan hotel

- Russian midgets in a living room on 100th street

quarreling elderly couple on a park bench- New Orleans bartender at home with a souvenier dog

- Central Park boy with toy hand grenade

- Brassai

- 1912 Lartigue "Racecourse at Nice" woman in plumed hat and veil

- Wikipedia on Lartigue

(I believe this is the photo she is referring to.)- Arbus's "Woman with a Veil on Fifth Avenue, NYC, 1968"

- Examples:

Frontality in Ceremonial Pictures,

Billboard ads with side view,

Jawaharlal Nehru

three quarter view for politicians- Tod Browning Freaks (1932) wedding scene

- Sylvia Plath suicide 1971

- Reich's definition of a Masochist

- Reik, Theodor. “THE CHARACTERISTICS OF MASOCHISM.” American Imago, vol. 1, no. 1, 1939, pp. 26–59. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26301144. Accessed 6 Aug. 2020.

- Thalidomide babies

- Napalm victims

- Nathanael West

- Fellini, Arrabal, Jodorowsky, underground comics, rock spectacles

- Coney Island freakshow outlawed early 1960s

- Time Square drag queens 1970s

- Vogue 1970s

- Wikipedia on Dante

- Paul Morrissey

- Warhol Chelsea Girls (1966)

- Hobbesian man

- Weegee

- Brassai La Mome Bijou 1932

Lewis Hine "Mental Institution, New Jersey, 1924"- Walker Evans 1946 Chicago street

- Robert Frank

- Giorgio Morandi still lifes of bottles

- Stieglitz as Don Quixote page 47

"Melancholy Objects" (Page 51-82)

- Surrealism

- Surrealism is : "Psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express—verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner—the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern." --Andre Breton in the "Surrealist Manifesto" (1924)

- Wikipedia on Surrealism

- The Met on Surrealism

- Tate on Surrealism

- Jackson Pollock

- beaux arts painting

- trouvailles of the 1920s

- Solarized photos and Rayographs of Man Ray

- Photograms of Lazlo Maholy-Nagy

multiple exposures of Bragaglia- photomontages of John Heartfield and Alexander Rodchenko

- sewing machines and umbrella

- "as beautiful as the chance encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on an operating table." from Les Chants de Maldoror (1869) by Lautreamont

- Wikipedia on the poet Comte de Lautreamont

- Wikipedia on Les Chants de Maldoror

Sewing Machine with Umbrellas Salvador Dali (1904-1989)- 1888 Kodak Ad Push the Button

- The Cameraman (1928) by Buster Keaton

- 1850s Surrealist photos

- Freudianism

- Baudelaire's flaneur

- Paul Martin candid snapshots 1890s

- London street

- seaside

- Arnold Genthe

- San Francisco's Chinatown

- Atget

- twilight paris

- Brassai Paris de Nuit (1933)

- Weegee Naked City (1945)

- Naked City on AbesBooks

- Steve Kasher Gallery Exhibition of Naked City

"Their First Murder, 1945" by Weegee- Jacob Riis again

- East 100th Street, Bruce Davidson, 1970

- Society for Photographing the Relics of London (1874-1886)

- Wikipedia on the Society

"Saint John's Gate, Clerkenwell, the main gateway to the Priory of Saint John of Jerusalem," black and white photograph by the British photographer Henry Dixon, 1880.- National Photographic Record Association

- Founded in 1897 by Sir Benjamin Stone

- Count Giuseppe Primoli

- King Viktor Emmanuelle's Wedding

- Naples Poor

- Jacques-Henri Lartigue

- Street Life in London by John Thomson (1877-78)

- 36 images

- Illustrations of China and its People (1973-1874)

- Vogue of At home Portraiture (1880)

- Edward Steichen

- Henri Cartier-Bresson

- Richard Avedon

- Bill Brandt

- Depression Squalor Northern England

- Celebrity post war

- semi-abstract nudes

- Lewis Carroll little girls

- Diane Arbus Halloween crowd

- Ghitta Carell

- Mussolinni photos, Celebrity

- Surrealist Photographer Cecil Beaton

- Edith Sitwell 1927

- Cocteau 1936

- August Sanders

- 1911 Starts Photographic Catalogue of German People

"Young Farmers" (1914) from The Tate- Antlitz der Zeit (The Face of our Time) (1929) (destroyed by the Nazis in 1934)

- landscape photography

- George Grosz' drawings, Weimar

- August Sander "Circus People" (1930)

- Diane Arbus circus people

- Lisette Model's demimonde characters

- Edward Muybridge

- Wikipedia on Muybridge

- How horses gallop

- how people move

- August Sander subjects

- 184 of Sander's images at The Tate Museum

- 718 of Sander's images at MOMA

- bureaucrats

- peasants

- servants

- society ladies

- factory workers

- industrialists

- soldiers

- gypsies

- actors

- some photos are casual, fluent, naturalistic

- others naive, awkward

- professionals and the rich tend to be photographed indoors

- laborers and derelicts outside with props

- cretin

- bricklayer

- legless WWI vet

- healthy young soldier in uniform

- scowling Communist student

- smiling Nazi

- captain of industry

- opera singer

- American Photographs by Walker Evans (1938)

- The Americans by Robert Frank (1959)

- FSA 1935 Edited by Roy Emerson Stryker

- Adam Clark Vroman

- Indian Photographs 1895-1904

- Lewis hine and the National Child Labor Committee

- photos of children in

- cotton mills

- beet fields

- coal mines

- Stryker's FSA

- migrant workers

- sharecroppers

- Thomson's detached travel reports

- Riis and Hine

- Hine interview, 1920 "Treating Labor Artistically"

- 1869 Westward colonization through photography

- Tourist views of Indian Life "Good Shot"

- Holy Objects

- Sacred Dances

- Paying the Indians to Pose

- Mulberry Bend by Riis (1880s)

- Inhabitants rehoused by Theodore Roosevelt

- Hart Crane writing about Stieglitz in 1923 "Speed is at the bottom of it all" "Moment made eternal"

- Kodak Photo spots

- signs in towns of what to photograph

- marked places in national parks

- Henry James in the American Scene 1907

- Jack Kerouac's introduction to Robert Frank's The Americans

- Clarence John Laughlin (1930s) "extreme romanticism"

- Plantation houses of lower Mississippi

- Funerary monuments in Louisiana swamp burial grounds

- victorian interirors in Milwaukee and Chicago

- "Spectre of Coca-Cola" 1962

- Bernice Abbott

- Changing New York (1939) (preface)

- Rilke The Duino Elegies

- Tableaux out of refuse

- Kurt Switters,

- Bruce Conner,

- Ed Kienholz

- Robert Venturi, architect, Time Square

- Reyner Banham lauds LA

- William H Fox Talbot 1830s

- "injuries of time"

- Roman Vishniac

- daily life in the Ghetooes of Poland, 1938

- Stereotyped photographs cupped behind glass and affixed to tombstones in the cemeteries of Latin countries

- Robert Siodmak's film Menschen am Sonntag (1929)

- La Hetee by Chris Marker (1963)

- Recent book arranges photos of celebrities as children

- Stalin and Gertrude Stein

- Elvis Presley and Proust

- Hubert Humphrey (age 3) and Aldous Huxley (age 8)

- Down home by Bob Adelman (1972)

- Let us now Praise Famous Men by Walker Evans and James Agee

- Wisconsin Death Trip by Michael Lesy (1973)

- 1890-1910

- found objects

- photos by Charles Van Schaick

- Glass negatives at State Historical Society of Wisconsin

- aleatoric

- John Cage music and choreography by Merce Cunningham

- Sherwood Anderson Winesburg, Ohio (1919)

- Hannah Arendt essay on Walter Benjamin

- Viollet-le-Duc 1842 daguerreotypes of Notre Dame, restoration

- Marxist/Brechtian

- Second Hand Store as surrealist temple (Breton)

- Borges, Kitaj, Godard (quotation in Fiction, Painting and Film)

- Leonardo's The Last Supper

- 18th century beauty of ruins

- Laughlin photographs of decrepitude

- Joseph Cornell magic boxes filled with incongruous small objects

- movie still hoard

- kitsch

"The Heroism of Vision" (Page 85-112)

- Fox Talbot 1841 Patent "calotype"

- PDF Transcription of Talbot's 1841 Patent obtained from None Such Silver Prints where you may also find an account of the whole invention process. The Nonesuch account of Talbot's invention is quite charming.

- Kalos

[The Oriel Window, South Gallery, Lacock Abbey] (1835) from the Met Museum collection. This is one of the earliest known photographs, and is a negative image of a window in the Abbey where Fox Talbot lived.- Exposition Universelle (1855)

- Wikipedia on the Exposition

- Finishing the Negative (on Victorian Photo Retourching) (1901)

- The House of the Seven Gables by Nathaniel Hawthorne (1851)

- le beau c'est le vrai

- Emile Zola "In my view you can not claim to have really seen something until you have photographed it."

- Talbot's own account, The Pencil of Nature (1844) Lake Como italian

- Breton essay in 1920 about Max Ernst "photography of thought"

- French Daguerrotypes of the Pacific, 1841

- Excusions daguerrienes: Vues et monuments les plus remarquables du globe published in Paris 1841

- 1850s orientalism

- Maxime Du Camp in the middle east with Flaubert 1849-1851

- Colussus of Abu Simbel

- Temple of Baalbek

- Painting, Photography, Film by Moholy-Nagy (1925)

- Alfred Stieglitz February 22, 1893 "Fifth Avenue, Winter"

- Fox Talbot Subjects

- Portraits

- Domestic Scenes

- LandScape

- Still Life

- Seashell

- Wing of Butterfly

- two rows of books in study

- Paul Strand in 1915

- "Abstract Patterns Made by Bowls"

- 1917 close up of machine forms

- 1920s close up nature studies

- 1920-1935 close ups

- nudes

- tiny cosmologies of nature

- Moholy-Nagy's Von Material zur Architektur (Bauhaus, 1928)

- (Translated into English as The New Vision)

- Albert Renger-Patzsch Die Welt ist schon (The World is Beautiful) (1928)

- colocasia leaf

- potter's hands

- Abstracting eye between the two Great Wars by

- Strand

- Edward Weston

- Minor White

- Kandinsky

- Brancusi

- Cubist hard edge opposed to the softness of Stieglitz

- 1909 Stieglitz on Photography and Painting in Camera Work (impressionism)

- Weston's "Cabbage Leaf" (1931)

- Harold Edgerton splash of milk (1936)

- Thoreau "You can't say more than you can see." (quoted by Paul Strand)

- Turner born in 1775, Talbot in 1800

- Francis Bacon and Warhol used Photography

- The visual quality of poetry by

- Apolinaire

- Eliot

- Pound

- William Carlos Williams ("No truth but in things")

- Blakean task of "Cleansing the senses"

- Pound "Make it new"

- Weston's diaries, Daybooks

- D.H. Lawrence

- William Ivins Jr. (Hunting for distortion)

- Peppers, by Weston 1929, 1930

- metullurgy photography

- crystallographers

- scientific microphotography

- Weston toilet bow Mexico 1925

- snowflake

- coal fossil

- Andre Kertesz

- Bill Brandt

- Cartierr-Bresson

- Robert Frank (democratic)

- Strand and Weston Subjects (close ups)

- plants

- shells

- leaves

- time weathered trees

- kelp

- driftwood

- eroded rocks

- pelican wings

- gnarled cypress

- gnarled worker hands

- pregnant woman so that her body looks like a hillock

- a hillock so that it looks like the body of a pregnant woman

- Aaron Siskind

- Architecural

- street people

- Ansel Adams

- Andreas Feininger's The Anatomy of Nature (1965)

- Weston "Torso of Neil" (1925)

- Jacob Riis 1887-1890

- "Wrong framing"

- blunt contrast

- Greek youth beauty

- Greta Garbo

- Strand "Blind Woman" and "Man" 1916

- Helmar Lerski's Kofe des Alltags (Everyday Faces) (1931)

- beggars

- street sweepers

- vendors

- washerwomen

- Richard Avedon fashion photography

- 1972 Avedon's dying father

- Cordelia (Lear)

- W. Eugene Smith Japanese fishing village of Minamata (1960s)

- Mercury poisoning

- dying girl in Mother's Lap

- Pieta

- Artaud's Theater of Cruelty

- Wittgenstein "meaning is use"

- The Death of Che

- John Berger on the photo of Che Guevara's Body

Bolivian photo of Che Guevara's body, October 1967

Mantegna's "The Dead Christ"

Rembrandt's "The Anatomy Lesson of Professor Tulip"- Walter Benjamin address in Paris at the Institute for the Study of Fascism (1934)

A Letter to Jane by Godard and Gorin (1972)- Jane Fonda in L'Express

- 1943 photo of jewish boy in Ghetto rounup Warsaw...

- Wikipedia on Bergman's Persona

- Lewis Hine

- American Mills and Mines exploited children

- Paul Strand

- bowery derelict

- Mexican peon

- New England farmer

- Italian Peasant

- French artisan

- Breton or Hebrides fisherman

- Egyptian fellahin

- village idiot

- Picasso

- Cartier-Bresson

- china

- Robert Frank

"Photographic Evangels" (Page 115-149)

- Delacroix on photography in 1854

- Nadar Portraits

- Avedon Portraits

- Nadar's Portraits of

- National Portrait Gallery of the UK Nadar Collection

- Baudelaire

- Dore

- Michelet

- Hugo

- Berlioz

- Nerval

- Gautier

- Sand

- Delacroix

- Complete Works of Eugene Delacroix

Delacroix's portrait of George Sand

Delacroix's portrait of George Sand

- Zen Archer

- Ansel Adams

- Paul Rosenfeld's chapter on Stieglitz in Port of New York

- Harry Callahan

- Bernice Abbot

- Denunciation of Pictorial photography

- Pictorial Effect in Photography by Henry Peach Robinson (1869)

- "Heightened reality" Moholy-Nagy

- "in-between moments" Robert Frank

- "de-familiarized" Viktor Shklovsky

- Moholy-Nagy 1936 Essay

- Stieglitz cloud studies 1920s

- Harold Edgerton's high speed photographs of bullets

- swirls and eddies of tennis strokes

- Lennart Nilsson's endoscopic photos of body interiror

- Not using Fancy Equipment:

- Weston

- Brandt

- Evans

- Cartier-Besson

- Frank

- Alvin Langdon Coburn

- "fast seeing" 1918

- Nostalgic media:

- daguerrotypes

- stereograph cards

- cartes de visite

- family snapshots

- early 19th and 20th century commercial and provincial photographers

- Hologram

- Heliogram (cameraless photos made in the 1820s by Nicephore Niepce)

- Henry Peach Robinson "Photography is an art because it can lie."

- The Decisive Moment by Cartier-Besson (1952)

- John Szarkowski "a skillful photographer cn photograph anything well"

- Abstract Expressionism

- Todd Walker's solarized photographs

- Duane Michal's narrative sequence photos

- Eakins and the male nude

- Laughlin and the Old South

- Careers with sharpest break in style

- Stravinsky

- Picasso

- Stravinsky:

- Le Sacre du printemps

- Dumbarton Oaks Concerto

- late neo-Schoenbergian works

- Muybridge:

- studies of human and animal motion

- photo expeditions to Central America

- government sponsored camera surveys of Alaska

- Yosemite

- "Clouds" series

- "Trees" series

- Atget:

- Trees

- Paris shop windows

- Roman Vishniac

- pre-war portraits of Polish Jews

- Scientific microphotographs since 1945

- Avedon's portraits (white backgrounds and flat lighting)

- Grisaille of Atget's Paris street studies

- Irving Penn

- Celebrities

- Food

- for fashion magazines and ad agencies<

- Show in 1975 at MOMA

- series of cigarette butts

- Nominal subject

- profoundly banal

- Man Ray

- photographic/painterly norms

- Steichen

- Abstractions

- portraits

- ads for consumer goods

- fashion

- aerial reconnaissance in military

- Pictorial "soft focus"

- Cameron

- Stieglitz

- Cigarette Butts

- Bas Stations

- Turned Backs

- Vocabulary of Painting:

- composition

- light

- so forth

- T.S. Eliot

- "each important new work necessarily alters our perception of the past"

- Arbus helps us appreciate Hine "opaque dignity of victims"

- Westonism

- "photography considered as an independent visual exploration of the world with no evident social urgency"

- Technical perfection of Weston

- calculated beauty of White and Siskind

- poetic constructions of Frederick Sommer

- self-assured ironies of Cartier Bresson

- Pictorialists from another era

- Oscar Gustav Rejlander

- Henry Peach Robinson

- Robert Demachy

- Modernism elevated Donne

- Diminished Dryden

- 1870s abandoned children admitted to Doctor Barnardo's Home (records)

- David Octaviius Hill's complex portraits of Scottish notables of the 1840s

- Weston's classic modern not diminished by

- Benno Friedman's pictorial blurriness

- Atget vs Weston

-

- Stieglitz and Photo-Secession

- Weston and f64

- Renger-Patsch and the New Objectivity

- Walker Evans and the FSA

- Cartier-Bresson and Magnum

- Baudelaire:

- Photography was Painting's mortal enemy

- The Centenary of Photography (1929) by Valery

- Mario Praz

- Painting became

- telescopic

- microscopic

- photoscopic

- Painters used photos as visual aids

- Delacroix

- Turner

- Picasso

- Bacon

- (girl with Pearl Earing)

- Christo's packaging of the landscape

- Earthworks of

- Walter De Maria

- Robert Smithson

- Language can make

- Scientific discourse

- love letters

- grocery lists

- Balzac's Paris

- Photography can make

- passport pictures

- weather photographs

- pornographic pictures

- X-Rays

- Wedding photographs

- Atget's Paris

- Media:

- Film

- TV

- Video t

- ape-based music of Cage

- Stockhausen

- Steve Reich

- Marshall McLuhan

- "The Medium is the Message"

- Pater

- "All art aspires to the condition of music"

- Now

- "All art aspires to the condition of photography"

"The Image-World" (Page 153-180)

- The Essence of Christianity by Feuerbach (1843) Second Edition Preface

- "Our era prefers the image to the thing, the copy to the original, the representation to the reality, appearance to being"

- Second Edition Preface

- "If only Holbein had lived long enough to do a portrait of Shakespeare."

- Holbein the Younger (1497-1543)

- Wikipedia on Holbein

- Portrait of a Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling, c. 1527–28.

- Shakespeare (1564-1616)

- 1823 image from First Folio, by Martin Droeshout

- Wikipedia on Nail from the True Cross

- E. H. Gombrich on images in primitive stories

- Delacroix's Journal, (1850)

- Photography at Cambridge observation

- French Edition

- English Edition (large PDF)

- infrared photography

- holography

- Kodak development

- Polaroid

- Cinema

- Video

- Nadar on Balzac's fear of photography (1900)

- Balzac's prose

- Erich Auerbach's Mimesis

- Le Pere Goriot (1834) by Balzac

- French Edition

- English Edition

- French Edition

- Jude the Obscure

- "it seemed like a movie"

- plane crash

- shoot-out

- terrorist bombing

- Hardy Bridehead

- photography of Sue (Search the above Google Edition of Jude the Obscure for "sue photograph" to see all the citations).

- Cocteau's Les Enfant's Terrible

- Wikipedia on Les Enfants

- brother and sister bedroom with images of

- boxers

- movie stars

- murders

- Cell no. 426 Fresnes Prison

- 1940s

- Jean Genet pasted

- twenty criminals clipped from newspapers

- "Our Lady of Flowers"

- J.G. Ballard's novel Crash (1973)

- Thomas Mann's The Magic Mountain

- pulmonary x-rays

- Claudia Chauchat x-ray portrait

- Proust's realism

- Swann's Way

- disparaging of photographs as "shallow" (Check out pages 51 and 52. Or just search "photograph")

- Pierre by Melville (1850s)

- Nabokov Invitation to a Beheading (1938)

- photohoroscope

"A Brief Anthology of Quotations" (Page 183-208)

I have not yet decided how exactly to annotate this.

Did Sontag steal all her best ideas from The Kinks? Scholars remain divided. (SATIRE) (Otherwise known as: Sontag's ideas in other places)

The Kinks say:

Or, as Sontag would say:

"It is a nostalgic time right now, and photographs actively promote nostalgia. Photography is an elegiac art, a twilight art. Most subjects photographed are, just by virtue of being photographed, touched with pathos. An ugly or grotesque subject may be moving because it has been dignified by the attention of the photographer. A beautiful subject can be the object of rueful feelings, because it has aged or decayed or no longer exists. All photographs are memento mori. To take a photograph is to participate in another person's (or thing's) mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time's relentless melt." (15)

To which, The Kinks reply:

And Sontag says:

"As photographs give people an imaginary possession of a past that is unreal, they also help people take possession of space in which they are insecure. Thus, photography develops in tandem with one of the most characteristic of modern activities: tourism." (9)

"Taking photographs fills the same need for the cosmopolitans accumulating photograph-trophies of their boat trip up the Albert Nile or their fourteen days in China as it does for lower-middle-class vacationers taking snapshots of the Eiffel Tower or Niagara Falls." (9)

"Ultimately, having an experience becomes identical with taking a photograph of it, and participating in a public event comes more and more and more to be equivalent to looking at it in photographed form. That most logical of nineteenth-century aesthetes, Mallarme, said that everything in the world exists in order to end in a book. Today, everything exists to end in a photograph." (24)

Other stuff

My Main Website where you can learn about me.

The Vernacular Photography of Gerald Grossman

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg!Large.jpg)